The Grove – does Bamburgh’s green hide a secret?

Pre-historic Bamburgh

What language did people speak in Bamburgh at the time of Aidan and Oswald?

There is not a great deal written about the people of Bamburgh and their way of life during the time of Aidan and Oswald. These notes are an attempt to describe how the way people then spoke was a direct result of historical events of the period. It is impossible to separate the two. The information which follows aims to explain the very different groups of people who came and settled around Bamburgh during the first millennium, in particular, during the 5th to 7th centuries, a time of great change and progress and one which was fundamental to the North-East becoming a centre of learning not just in England but in the whole of Europe.

Early times in Bamburgh

At this time life for people in and around Bamburgh was changing in all sorts of ways. Bamburgh had been occupied by Brittonic/Brythonic. (British) speaking people that we used to refer to as Celtic (though archaeologists today often avoid this term as it does not appear to be how these ancient peoples viewed themselves). By the fifth century AD, Roman authority over Britain was at an end and regional communities were beginning to assert power over their individual areas. It was in into this changing landscape that migration of settlers from northern Europe appears to have occurred, settling in particular along the North-Eastern coast and as far south as modern East Anglia. It has been suggested those who came to Northumberland arrived via Lindsay in Lincolnshire giving the name of Lindisfarne to the island, however, no clear historical evidence has been found for this. Use of Latin and the native Brittonic languages continued by the people who remained. Latin was the language of law and education but it was less spoken in the rural north where Celtic Brittonic was used within the family and immediate neighbourhood.

For generations, the few historical records that survive from this early time were all that was available to tell the story of the post-Roman period. Even once archaeology was able to make its contribution it was traditionally interpreted within this historical framework. This historical version of the time was that Anglicans and Saxons established kingdoms in the south and east, Brittonic kingdoms continued to dominate in the west. annals talked of Anglians arriving at Bamburgh in the latter part of the 5th century. Bede, the Benedictine monk at the monastery of Jarrow, who wrote the first history of this country, gives the date as 449 AD. Known as the Father of English History, he provides much of the information which informs our knowledge of this period. Born in 672, Bede began the tradition of literature which went on to flourish in the atmosphere of Northumbria of that time and was unequalled in Europe

The Anglians

After defeating Outigern the Brittonic leader and capturing the fortress at Din Guaroi, the original name for Bamburgh, Ida, became from 547 the first Anglian king of the area which later became Northumbria under the rule of his grandson, Aethelfrith. Ida settled at Din Guaroi (now Bamburgh) on the coast and it is not difficult to see why he chose this strong, distinctive, elevated location overlooking the sea and nearby islands of the Farnes and Lindisfarne. The settlement of Din Guaroi became known as Bebbanburh after Aethelfrith’s wife, Bebba. Eventually, this became known as Bamburgh. There was intermittent resistance to the Anglians from the native Brittonic people which subsided as the Anglians increased their power despite being the minority culture during their early years here. Their influence was such that they became the more powerful group and their culture and way of life was gradually adopted by the settled majority. This included the language they spoke. However, it is important to note that Bede claims English, Pictish (in Scotland), Brittonic and Latin were all still being spoken as late as the 8th century.

An archaeological story

Even before more modern science-based evidence became widespread there were dissenting voices in the archaeological community that saw a different story that could be told from the archaeological evidence. The ‘tribal’ groups of Angles, Saxons and Jutes were not apparent in the material culture seen in cemetery excavations in different regions, nor in the pottery excavated from various settlement sites. This led to a different school of thought for the migration period, accentuating the continuity of population and slowly introduced cultural change.

In recent decades this excavated evidence has been greatly added to by isotope data, that tells us where people grew up, and DNA evidence that gives us a window into ancestry. This new evidence tells us that migration has been continuous from prehistory to the present and if greater levels of immigration did occur in the post-Roman period It was never sufficient to be more than a minority of the population. Bede’s idea of the people of Northumbria being of the Anglian race is now clearly a creation myth and it is very likely that the continental immigration into the far north of England was very modest.

Origins of the English language

The term Anglians derives from the area known as Anglia (roughly corresponding to Schleswig-Holstein or the Frisian coastal region), the peninsula in the Baltic Sea which also gives us the word for the language they brought with them- Ænglisc, later becoming known as English. It was closely related to the Frisian and Low Saxon dialects of West Germanic languages. The new arrivals would have spoken this amongst themselves and as they gained power it would come to be adopted by the indigenous people.

When the Anglians arrived at Bamburgh they and the native people would be mutually incomprehensible. Although Brittonic and Old English both stem from the Indo-European family of languages, their grammars and vocabulary were quite different. Proto Indo-European was the ancestral tongue of most modern languages of Europe and had been spoken by nomadic peoples probably about 5000BC although there is little consensus about the precise period covered. From it various dialects developed and became the beginnings of the main European languages we know today. The Brittonic language was in use from before the Roman invasion and was spoken everywhere in what is now Great Britain which lay south of the Firth of Forth. It absorbed some Latin vocabulary during Roman rule. However, the new arrivals, the Anglians and other incoming tribes such as Jutes and Saxons, spoke Germanic languages which had developed in a different direction from Brittonic. During the fifth and sixth centuries, as the Anglians became the dominant group, the use of Brittonic faded and Old English, sometimes known as Anglo-Saxon, was to become the principal language of the area.

Old English used 4 different dialects, Northumbrian and Mercian (Anglian) and Kentish and West Saxon (Saxon). Many of the earliest written texts from the late 7th century, such as Caedmon’s Hymn, were written in Northumbrian from which the Scots language later developed. By the beginning of the 7th century, Anglo Saxon was spoken all over the country apart from Cornwall, North-West England and Northern Scotland where the Celtic languages were more resistant to change.

Violent times give way to peace and the introduction of Christianity

Aethelfrith’s major achievement was to unite the two kingdoms of Bernicia (the northern lands of what are now SE Scotland, Northumberland and Durham) and Deira (Yorkshire). After he was killed in 616, his wife, Acha, and sons fled from Bamburgh for their own safety eventually settling on the island of Iona, off the west coast of Scotland. The throne of Northumbria was regained by Edwin. Acha and her sons remained on Iona for many years where they were influenced by the development of Celtic Christianity brought to that island by Irish monks. Oswald, the eldest son, was trained in different styles of martial combat and when he returned to conquer Northumbria he brought with him men of both Christian and pagan traditions. He became King of Northumbria in 634 and was swift to implement a means of introducing Christianity to the people of his lands. The Irish form of Christianity was to create monasteries in rural areas whereas the Roman form favoured towns. To this end, Oswald asked for a monk from Iona to be sent to establish a monastery in North Northumbria. The first missionary to arrive was Corman who achieved little success in his task. He did not win over the Northumbrians whom, on his return to Iona, he described to his superiors as:

“An ungovernable people of an obstinate and barbarous temperament…..who refused to listen to him.”

Aidan arrives in Northumbria

Aidan was then dispatched from Iona and was to achieve outstanding success, attributed to his willingness to mix with all types of people from all social sectors. He went everywhere on foot, even journeying into the Cheviots to meet with isolated shepherds. His many strong personal qualities contributed greatly to his achievements. It was Aidan himself who chose Lindisfarne as the place to build a monastery, possibly because its solitude and location reminded him of Iona. However, he began his work in Northumbria with a major disadvantage – that of not being able to speak the native tongue. For Aidan spoke Gaelic and Latin but not English, which was now becoming dominant over Brittonic. Oswald was the ideal person to act as his interpreter, competent in Old English and having learnt Irish during his years in exile. Working as a pair, they were understood by everyone. The fact that people heard the word of God from the lips of their king was a powerful factor in convincing them to adopt Christianity. For the first time, they encountered a man able to read the written word rather than rely on memory and oral repetition and this helped Aidan to win them over. The people of Bamburgh, as elsewhere in Northumbria, were absorbing not just the tools of Old English but also the styles of music, food and dress of the Anglians, which complemented the more homely nature of their form of Christianity. But Latin had not yet disappeared since people who converted to Christianity would become familiar with Latin by reciting psalms. Moreover, many Northumbrians went on to learn Latin as they aspired to write in it.

Nowadays there are few remnants of Celtic life surviving in and around Bamburgh compared with places further west. Names of rivers, hills and trees are amongst these, such as the elements der/dar/dur and -went, usa – water (Ouse), briwaa – bridge and tor – hill, dun – hillfort, warn or fearn (alder) as in Waren Burn. A small number of names like Cheviot, Amble, Mindrum and Yeavering are attributed to the Celts.

The Anglians brought with them new words which were quickly absorbed by the indigenous people. These included:

Words for days of the week such as:

Monandaeg, Tiwesdaeg, Wodnesdaeg, after early Saxon gods.

Words for family members such as:

cild child, bearn bairn, broder brother, dohtor daughter, speoster sister, sunu son, ealdorfaeder grandfather, ealdormodor grandmother.

The most important area of influence on speech was that of domestic vocabulary such as names of items of food.

aeppel apple, milc milk, hroof roof, cirice church, bed bed, lufian to love.

Prepositions, numbers, and words that provide the structure of our language such as

biforan before, to to, tellan tell, morgen morning, whoet what, hwoenne when, hwoer where, hwelc which, giese yes, na no.

Are another legacy of Anglo Saxon. It is estimated that about 70% of the words we use in Standard English today are of Anglo-Saxon origin.

Anglo-Saxon place names

It is sometimes assumed that the Vikings settled in what is now Northumberland. Although a few place names of Scandinavian origin exist – Akeld, Lucker, Howick– they form a tiny minority. However, place names of Anglo-Saxo origin abound. The area around Bamburgh shows strong evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlement by the proliferation of Anglo-Saxon linguistic features Here are some local examples:

Beal – behil Old English (OE) beo-hull = bee hill, where bees swarm.

Shoreston – schoteston OE sceot = a personal name meaning quick.

Budle – bolda OE both = dwelling.

Elwick – ellewich OE Ella =of Ella + wic from Latin vicus +dwelling, dairy farm, hamlet.

Spindleston – spilestan OE spinele = spindle lock.

Outchester – ulecestr OE ule = owl + cestr = camp, Roman Fort i.e. Roman Fort inhabited/haunted by owls.

Beadnell – bedehal OE Beda personal name + halh = corner of flat land near River i.e. haugh.

Belford – beleford OE denu = dene + Ford of Bella.

Other settlements named after individual persons include Ellingham (Ella), Branxton (Brannoc), Chatton (Ceatta), Kimmerston (Cynemaer), Doxford (Dooc), Whittingham (Hwita), Mousen (Mul), Pegswood (Peg), Warkworth (Werce).

Personal names

The Anglians did not repeat names for people. Each person had a unique personal name, often adding prefixes to a core for one’s children. Personal names which survive to this day include Alfred, Cuthbert, Edward, Harold, Wilfred, Dunstan, Oswald, Oscar, Audrey, Edith, Ethel, Hilda, Mildred and Elfrida. Many other names have disappeared such as Hereward, Sunngifu, Wassa and Ealdgud.

It is said that all our 100 Key Words of Modern English are of Anglo-Saxon origin. So, children who learnt to read in the 1960s with the Ladybird Reading Scheme (Peter and Jane), which employed a Key Word approach, received a firm grounding in the Anglo-Saxon structure of our language. However, it is believed that over 85% of words used in that time died out with the later influence of the Vikings and Normans. As its grammar has become simpler in Modern English, so has its vocabulary expanded from a fairly restricted range in the 7th and 8th centuries.

Features of Anglo-Saxon (Old English)

It is not just the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary which has survived; the grammar has also been influential. Anglo Saxon provides us with our method of forming plurals and verb formats. Like modern German, it was a heavily inflected language with word endings changing to match the purpose of the particular word in a sentence:

Ic lufe – I love

Du lufast – you love

He lufad – he loves

He lufode – he loved

There were also irregular verbs such as:

Beon – to be

Ic eom – I am

Du eart – you are

He is – he is

We sint – we are

He waes – he was

As Old English evolved it became prestigious to be able to speak it without reliance on Latin or Brittonic and it played a role in bringing together the previously separate kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira, dissolving existing barriers between the two peoples.

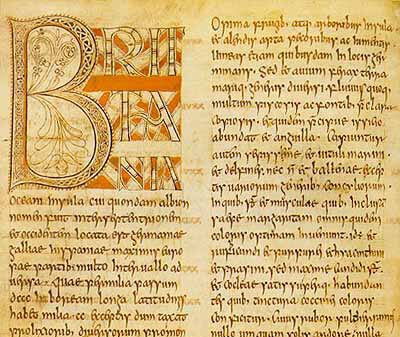

The written form of Old English initially employed runes angular marks designed to be impressed into the writing surface. As Christianity grew, early missionaries introduced the rounded Roman alphabet which was easier to read and to write on vellum.

Early Northumbrian Christianity was heavily influenced by the Celtic Irish tradition but as time went on the Roman model moved northwards. Each branch had its own method for selecting the dates of Easter which must have caused some confusion. Oswald’s successor, King Oiswiu, called the Synod of Whitby in 664 to determine which form to officially adopt. The Roman model was decided upon which resulted in most of the Irish missionaries returning to Iona, even taking some of the English ones with them. Many Anglo-Saxon missionaries remained and conformed to the Roman model.

The myth of the Vikings

The arrival of the Vikings from Norway and Denmark in the 8th and 9th centuries saw the Danish group settle south in what is now North Yorkshire as far as West Yorkshire and down the east coast to Lincolnshire and the Norwegian group enter by the West. Contrary to what is generally believed they did not settle in North Northumbria. Perhaps the story of the Viking raids on Lindisfarne has prompted and encouraged this myth. Nowhere is their pattern of settlement more evident than in the case of place names. Those of Danish origin, include thwaite – a clearing, by – town, stead, thorpe – outlying farm, toft – homestead. These elements are found in large numbers in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and the East Midlands but very rarely in present-day Northumberland. Throughout the latter are found the familiar Anglo-Saxon features such as:

beorg – hill as in Bamburgh.

denu – valley as in Loansdean.

wic – wick as in Berwick, Howick, Lowick.

dun – hill as in Bedlington, Cramlington, Rennington.

ingas – people of, as in Ellingham, Chillingham.

Scandinavian power prevailed until about 900 when it began to decline. In 1016 King Cnut took over the throne. More Scandinavian words were creeping into the English language but these were small in number. With the arrival of the Normans in the 11th century Old Norse and French words were added, with some replacing Old and Middle English words. Sometimes regional dialects preserved one form with English retaining the Old English form, e.g. (ON) Kirk and (E)church, (ON)garth and (E) yard.

And so, there are many and varied factors which influenced the development of the language which was the forerunner of Modern English. Had not the Anglians settled in the North East the speech of Bamburgh’s residents would have developed in entirely different directions. We know now that Northumbrian dialect is sometimes regarded as “the grandmother of English” and that while many features of this dialect have been lost from Middle and Modern English they live on in this region. If you have the opportunity to listen to recordings of Anglo Saxon as it is believed it would be spoken, you cannot fail to recognise familiar patterns of intonation, pitch and articulation as well as vocabulary still in common use today which you may hear amongst local people.

Spilic splint / spelk splinter

Claeg clay / claggy sticky esp. of mud

Faem foam, froth, weak / femmer fragile, feeble

Cuw cow / cow cow

Staener stony ground / stanners gravel beds formed into grassy haughs

Micel Great, big / muckle great, big.

Valerie Glass – October 2019