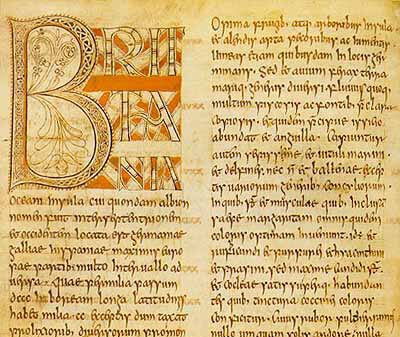

Languages in Anglo-Saxon Bamburgh

Captain Baker-Cresswell influences course of World War II

The earliest human activity in the Bamburgh area dates from the Mesolithic period (8,000 BC to 4,000 BC) that followed the end of the last ice age.

The population during this early period is usually perceived as small numbers of hunter-gatherers occupying temporary camps, often to be found by the sea and along river or stream courses. There are no certain Mesolithic flint finds from the castle site itself but they are present close by to its south. Although we cannot prove it, its easy to imagine hunter gatherers setting up intermittent camps on the bare castle rock where excellent views of the surrounding landscape would have been available.

There is no doubt that the fortress was occupied in the Iron Age and Roman period

Brian Hope Taylor in the 1960s and 1970s was able to excavate a number of modest sized trenches all the way to bedrock providing a full sample of the archaeology down to the earliest evidence. In his notebooks he talks of Iron Age pottery and finds encountered in the deepest layers beneath Roman Era finds. The Bamburgh Research Project has been fortunate to follow in Hope-Taylor’s footsteps and in small trenches reach early deposits in the Inner Ward of the castle and in recent months in the West Ward as well. There is no doubt that the fortress was occupied in the Iron Age and Roman period but we now know from a radiocarbon date that there was also occupation in the late Bronze Age around the 10th century BC. Its interesting to speculate that this prominent fortress could have been the home of some high status Bronze Age people that were buried in cists (stone lined graves) in the fields south of the castle on and around mounds that where once thought to be Bronze Age barrows.

The BRP has excavated a modest sample of layers from the Inner and West Wards down to bedrock and this includes some Iron Age to Roman period midden deposits. Animal bone was present in some quantity and was found to be mainly cattle but with some Red Deer. This suggests a good deal of beef was consumed in the late Iron Age and Roman period and also that hunting was occurring, something that may indicate a high status place occupied by the powerful just as it was in the early medieval period.

Early medieval Bamburgh

Bamburgh, like Edinburgh and Dumbarton, is believed to have been the focus of a British kingdom in the immediate post-Roman period (Higham 1993, 60). The site’s earlier documented name, Din Guoaroy or Guaire, is British in derivation. Bamburgh emerges as a central place in the historical record in the mid-sixth century and, by the beginning of the seventh century, it had become the pre-eminent centre of the Anglo-Saxon dynasty that came to dominate Northumbria. Stories of conflict between this dynasty and their neighbours and rivals, particularly a king of Rheged (probably Cumbria) called Urien is preserved in welsh language poetry. Whilst not the most reliable version of history it is quite possible that it does preserve a tale of warfare from the later 6th century, including a siege of Lindisfarne.

The importance and wealth of Bamburgh in the early medieval period is not in question

The historian David Rollason suggests that Bamburgh was fundamental to a ‘Bernician heartland’, and a focus for Northumbrian kingship, situated amongst a mixture of important inland and coastal settlements, such as Coldingham, Dunbar, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Yeavering. Bamburgh, in this period, has long been accepted as a royal centre based on Bede’s description of the site as an ‘urbs regia’. However, the importance and wealth of Bamburgh in the early medieval period is not in question. Its status in the seventh to ninth centuries is particularly evident through the use of stone architecture, as Hope-Taylor recovered evidence of a preninth-century mortar-mixer (Kirton and Young 2012, 251–8), indicating the early use of mortared stone buildings on the site. This is supported by the discovery of a stone structure, robbed before the twelfth century, in Trench 1 located in the West Ward and a second stone building and defensive wall in the Inner Ward. Jane Hawkes has argued that stonework in the seventh and eighth centuries would have been a rare occurrence, and its use in stone sculpture and the stone churches of Northumbria was a deliberate citation of the power of Rome and the Roman church.

Lying at the heart of the kingdom, Bamburgh despite its towering and impressive defences, was not often involved in conflict directly. Exceptions being a siege in the early 650s when Penda King of Mercia tried to burn is timber defensive wall and a further siege in 705 when it successfully sheltered the boy King Osred from rebel nobles who would have deposed him.

Bamburgh maintained its status as a principal royal centre until the fragmentation of Northumbria during the later ninth century (Rollason 2003, 258). From at least the early tenth century, a family of hereditary ‘earls’ ruled what remained of Northumbria along the eastern seaboard, north of the Tees, until the later eleventh century when they were replaced by earls of Norman origin (ibid, 249). The first named of these was called Eadulf and a surviving anal notes that he was a friend of King Alfred of Wessex, perhaps in alliance with him against the dangers of a Viking take over of all England. It is certainly that case that this dynasty was able to preserve Northumberland and County Durham as well as parts of the Borders as an English heartland despite the presence of powerful Viking kings centred on York, then called Yorvik. Indeed one of these Earls, called Oswulf was instrumental in bringing down the last Viking King of York, Erik Bloodaxe, resulting in the final unification of England as a single kingdom.

They even managed to resist the Norman Conquest for a time maintaining a high degree of independence. One of the reason it seems that the Norman record of the wealth of England that we know as the Domesday Book stopped at the Tees! This only delayed the inevitable as after 1076 they had been removed from power and replaced by Normal Earls the last of which Earl Robert de Mowbray, was removed from office in 1095 after rebelling, being captured and forced to surrender Bamburgh that was then under siege. Bamburgh was then taken into the direct ownership of the crown and remained a royal castle until it passed into private hands following the Union of the Crowns.